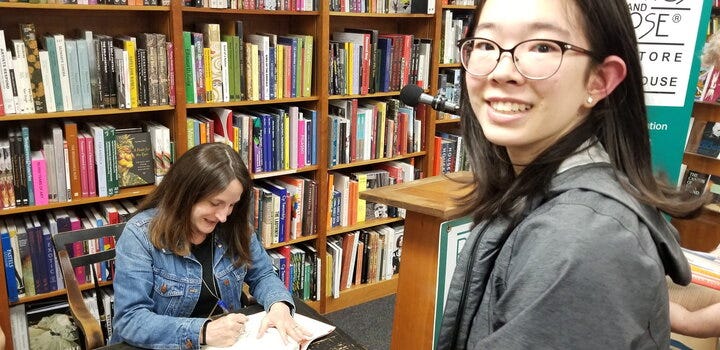

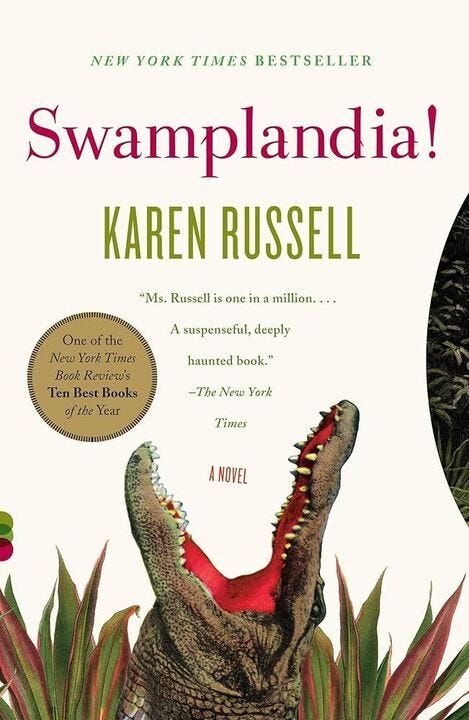

Spring is transitioning (rather suddenly here in Boston) into summer, and we’re hiring a new summer intern to help behind the scenes. We try to support our interns in their own projects to the extent that we can, so imagine our delight when we found out that Sydney Alexander, who interned for us for over a year, wrote her senior thesis at Middlebury College on magical realism, violence, and place as a joint project for the English and Geography departments! As you know by now, we’re tickled by works that blend disciplines or genres or perspectives. We asked Sydney to write up a little summary of her thesis. Read on for some of her insights into Karen Russell’s Swamplandia! and Gabriel García Márquez’ One Hundred Years of Solitude.

In Galiot book news, our interior designer sent us the first pass pages for Robyn Ryle’s SEX OF THE MIDWEST and they look… fantastic! Like a book! We’ll be sharing something of the interior design process in our next Substack. Meanwhile Emily Ross’s SWALLOWTAIL is now with the copyeditor, and Marian Donahue’s BACKSTITCH is going into the second round of revisions. And we are exploring possibilities for audiobooks. All this is the fun part! (Although admittedly some might argue that financial projections and valuations and pitch decks are fun, too.)

Magical Realism, Violence, and Place: an English and Geography Joint Senior Thesis

By Sydney Alexander

Last month, I defended my senior thesis, a project combining English and geography, my two majors. As a long-time fan of Karen Russell and of magical realist novels, I came in knowing I wanted to include one of her books in my senior thesis. Ultimately, I settled on a comparative study between her first novel Swamplandia! and Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s seminal magic realist text One Hundred Years of Solitude, realizing that Marquez’s novel — known for shaping conventions of magical realism as a genre — would be a useful entry point into Russell’s. I quickly noticed many similarities: both authors explore legacies of violence, are interested in the intersections of magic and gender, and are keenly attuned to place. Violence occurs primarily on two levels:on a larger scale, structural violence occurs as colonial-capitalist powers creep in from the wider developed world (the rival theme park World of Darkness in Swamplandia! and the American Banana Company in One Hundred Years of Solitude. On a more intimate scale, episodes of sexual violence against women occur in both novels.

In both books, solitude insulates native places against encroaching colonial powers and norms; Swamplandia!, a mom-and-pop alligator wrestling theme park on an island, is physically separated from the mainland by water, just as Macondo is tucked away into the Colombian jungle. This physical separation fosters differences, and in particular, allows for the reproduction of inverted or transgressive gender norms. In Swamplandia!, alligator wrestling is a very subversive work as the primary wrestlers of the Bigtree family are women. Hilola Bigtree, the mother, is the breadwinner of the family, relying on her physical prowess. Ava, the primary protagonist, is her understudy. Meanwhile, Chief Bigtree, the father, keeps things running from behind the scenes, working the lights, cleaning, and, after Hilola dies, caring for their children. This subversion of traditional norms relies on a distance from the mainland, where traditional values rule.

Kiwi Bigtree, the eldest child, further demonstrates this subversion. He begins the novel as an unlikely hero–scrawny, academically inclined, and uninterested in wrestling alligators. After the death of his mother, Kiwi goes to the mainland hoping for a job to support his family, particularly his two younger sisters. He begins at the World of Darkness doing feminized work, cleaning and lifeguarding, itself a form of childcare. However, when he saves a girl from drowning — playing out the narrative of a male hero rescuing a damsel in distress—he finds himself on a path to developing into a more traditional concept of masculinity, culminating in his becoming a pilot and saving his sister Ossie from the swamp. The mainland has shifted his gender identity toward a more normative masculine one.

“[it] was located in southwest Loomis County, just off the highway ramp…[it had] imbricating parking lots, a whole spooling solar system of parking lots. On its western edge, the Leviathan touched a green checkerboard of suburban lawns…the houses at the World’s perimeter look[ed] small and vexed. The World of Darkness offered things that Swamplandia! could not…Easy access to the mainland roads” ~Karen Russell, Swamplandia!

Physical separation also makes external forces clash with the particularities of a place’s natural conditions and resources. Colonial-capitalist powers extract labor and profit in acts of violence against smaller towns in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Late in the novel, the American Banana Company moves into Macondo, exploiting townsfolk for cheap labor and natural resources of the nearby jungle in order to grow bananas. Similarly, a significant arc in Swamplandia! follows the ghost of a dredgeman from 1920’s Florida who participated in a project to drain the swamp in order to convert the land into commercial real estate. In both cases, violence provokes a reaction from the natural world: a biblical storm lasts for four years after a massacre of banana workers, purging Macondo of its colonizers but also of any potential for prosperity; buzzards descend upon a dredge boat, killing several dredgeman and effectively halting their project of draining the swamp.

In both novels, the natural world is also connected to magic, femininity, and sexual violence. It is young girls who often have the deepest connections with the natural world and who thus have the greatest capacity for magic. Ava and Ossie Bigtree both embark on journeys deep into the wild, untamed landscape of the Florida Everglades; female sexuality is intimately connected with the natural world for characters including Renata Remedios, Pilar Ternera, and Petra Coates in One Hundred Years of Solitude. It is also often young girls — virgins — who experience sexual violence. Ava Bigtree follows the Bird Man into the swamp, believing that he is leading her to the Underworld where she will find her sister. However, late in their journey and after Ava figures out that the Bird Man has tricked her into believing in an Underworld — preying on her innocence and belief in magic — he rapes her, effectively destroying her conception of magic. Thus, while magic becomes a sort of defense mechanism for the natural world, it offers little to women against sexual violence. What is more, there seems to be a parallel between the corruption of secluded, lush natural landscapes by colonial-capitalist powers and the corruption of young girls. If both Marquez and Russell are interested in the dangers of colonial-capitalist forces destroying native places, then violence against women is an insidious yet apt comparison.

We are stepping up our social media game! Or at least trying to. Follow us on Insta or Facebook, if you still find yourselves in those spaces, and show us a little love! We’ll be on BlueSky soon as well.

Anjali & Henriette